- Home

- Britta Rostlund

Waiting for Monsieur Bellivier Page 4

Waiting for Monsieur Bellivier Read online

Page 4

Mancebo throws out all the words he can remember from Adèle’s sermon. Adèle sniggers. Fatima shakes her head. Tariq starts eating.

‘And where is our son supposed to sit when he comes in?’

‘The light comes from here … and the room is rectangular … the kitchen’s there, the rug is red … that’s where he’s got to sit,’ he exclaims, pointing to the corner where the TV is. ‘That’s where I want my son to sit when he comes home.’

Adèle hoots with laughter. Even Tariq laughs, and Mancebo can’t help but smile.

‘What are you saying, husband? Are you OK? How did you come up with all that? Are you crazy?’

Mancebo realises he must now calm Fatima down and reassure her that everything’s fine, so he kisses his wife’s perspiring brow.

‘No, I’m joking. Amir can sit wherever he wants, but a bit of a change doesn’t hurt. I mean, if Adèle’s into feng shui, I don’t see why we shouldn’t give it a try. It came to me when I overslept this morning. I started thinking about what Adèle said last week, when she told us feng shui could do wonders for a business, and I thought: why not give it a go?’

Mancebo is impressed with himself.

‘Sit down, you idiot, so we can eat before the food gets cold. Luckily for you, Amir isn’t coming for lunch today, so we can deal with this later.’

Mancebo would never have believed that such a seemingly pointless conversation with Adèle could have helped him out of this difficult situation. They start to eat.

‘You want me to ring Raphaël, then?’ Tariq asks, letting out a sound somewhere between a belch and a sigh.

‘No, I’ll do it.’

Mancebo gets up, dons his cap and is on his way out of the apartment when he remembers that he usually washes his hands after a meal. He can’t change his ways or they’ll suspect something. He remembers that he usually hums while he washes his hands. But what comes out of his mouth is a sound he’s never heard before. He’s forgotten what he usually hums, but he continues the tune he’s started. As he goes down the stairs, he feels the eyes of the others upon him.

An old man with a large red mobile phone is waiting outside the shop. Mancebo generally recognises his customers, unless they’re tourists, of course. This man seems at home in the city but not in the shop, perhaps not even in the neighbourhood. Mancebo greets him cheerily and switches on the little fan beside the till. He normally likes to chat with new customers, but today he feels only irritation. All he wants is to get on with his new job.

The man picks up a bottle of wine, some bread, cheese, olives and some little lemon cakes. An impromptu picnic, Mancebo guesses aloud, and the man nods. Maybe he isn’t such a bad detective after all. Of course, he’s spent his whole life around people. And how many hours has he spent on his stool, watching how they behave? That’s excellent groundwork for a detective. When the man places the olives on the counter the gesture reminds Mancebo of Madame Cat.

It feels like weeks since she came into the shop. The till jangles and as soon as the man leaves, Mancebo takes up his position again. He has spent years sitting on this stool. But now his intentions are very different.

The hours pass slowly, the sun drags itself across the sky. The radio tells the old and the young to stay indoors and drink water. No one has entered or left the building opposite, or not that Mancebo has noticed. He starts to despair. Maybe he’ll never get to begin the task that, in just a few short hours, has become the spice in his otherwise tasteless life.

As he pulls down his grille he realises he should hurry. He sees signs that he has delayed his afternoon break. Madame Brunette has already taken her poodle for its afternoon walk. The restaurant further down the boulevard has already bought its bread for the evening, and the light tells him he’s definitely half an hour late for his pastis. Tariq shambles over the road, picks out a wizened apple and pulls a face, and they set off for Le Soleil. The Sun, there’s no better name for a bar on a day like this.

‘This bloody heat,’ Tariq mutters between gulps.

‘No one should spend the summer in Paris.’

‘You’re right there. Did you know that in Saudi Arabia people have air conditioning in every room, even the tiny ones?’

They turn onto Rue Clapeyron, where tall buildings block the sun.

‘Well then, brother, did you call Raphaël?’ Tariq asks

‘No, I think the van’s working again now. Maybe it just had heatstroke.’

‘You sure? A van can’t just repair itself. You better take it for a test drive.’

‘Yes, OK, you’re right. I’ll do it after our drink.’

The last thing Mancebo wants is to take the van out, but he knows he has to stick to his story.

François shakes the cousins’ hands, and turns the fan in their direction.

‘For my VIPs,’ he says, setting down two glasses of pastis in front of them, one with ice and one without.

‘Mancebo’s van broke down,’ Tariq tells the bartender.

Mancebo is getting really fed up with this now. How can such a petty problem, a broken-down van that hasn’t even broken down, take on such proportions? Why can’t his cousin just drop it? Mancebo wonders why Tariq always tries to shoulder his burdens. Of course he’s grateful that Tariq fixes the grille when it jams, or helps him with his tax return, but this time the help is unwelcome.

‘Yeah, I couldn’t get out to Rungis this morning, but one day without fresh fruit and veg won’t ruin my reputation, will it?’

‘Give Raphaël a ring,’ is François’ suggestion.

‘That’s what I told him,’ says Tariq, draining his glass.

Tariq can’t stop talking on the way back. Mancebo says nothing. He feels slightly disappointed. Virtually a whole day has passed and there’s been no sign of the writer. Maybe he’ll never have anything to tell stories about. Mancebo feels deflated as he trudges back to the shop with Tariq, who is telling him about a tramp who handed in a pair of shoes for repair that morning.

The van splutters to life straight away, but he starts it a few more times, in case anyone should hear his clumsy attempts to check the engine. Mancebo sighs and pulls out into the heavy traffic. The air is still. It’s total madness to drive around for the sake of appearances when the radio is telling them all to leave their cars at home. Mancebo drives around the block. As he passes Le Soleil, François looks up from the bar. He waves and raises an eyebrow. Mancebo gives him a thumbs up and forces a big smile.

Though he is only a few hundred metres from his shop, he feels as though he’s discovering the neighbourhood for the very first time. For thirty years now, he has walked the block around his shop, but he’s never driven it in the van. There’s never been any reason to. Lost in thoughts of how different things look from behind the wheel, he takes a wrong turn up a one-way street. His fellow Parisians waste no time in alerting him to his mistake.

Mancebo raises a hand to acknowledge his error, mutters something and looks around for road signs which can lead him back to the safety of his boulevard. Sweat trickles from beneath his black cap. It’s as though that, too, has been waiting for the right moment to make an appearance. The tourists, maps in hand, are moving slowly.

Mancebo studies a group of pigeons relieving themselves on a balcony. Maybe they can’t fly and shit at the same time. He turns right, and to his relief sees the boulevard straight ahead. Then he sees the writer. He’s going down the fire escape with a sheaf of papers in his hand. Though he knows it achieves nothing, Mancebo toots his horn; it’s just a way of channelling his stress. He indicates to turn left into the boulevard, but swiftly turns right instead.

He has to seize this opportunity. The dense traffic now works to his advantage, it’s moving at a snail’s pace, which allows Mancebo to keep pace with the writer on the other side of the boulevard. He grips the steering wheel more tightly. The writer turns in to Rue de Chéroy and Mancebo whizzes around the roundabout to catch him up. This street is narrower, and Mancebo is now neare

r to the man. He can study the writer as he goes on his way, oblivious to the pursuit. Nothing in his face suggests a lover. Though exactly what would, Mancebo has no idea. A lipstick mark, perhaps? But that would be too obvious. Mancebo is trying to search for some other sign of infidelity when, suddenly, he hears a bang.

The steering wheel slams into Mancebo’s chest. He hadn’t even considered putting on his seat belt, he was only pretending to check the van was OK. Everything stops. Silence fills the van. Mancebo feels like he is looking straight into the writer’s eyes. He is one of the many people who have stopped in their tracks. The taxi driver Mancebo has rammed into, a smallish young man with a lot of tattoos, is already on the pavement.

Mancebo knows he has to get out and take responsibility. His chest hurts. He snatches the prayer beads hanging from the rear-view mirror but holds them behind his back. He does not want to be mistaken for a terrorist. He pushes the wooden beads along the string with his sweaty fingers. That was what his father always did when he was under pressure.

Suddenly, two traffic officers have appeared. Mancebo has no idea how they got there so quickly, but maybe they were already on the boulevard, giving out parking tickets. Both are standing at the ready with their notepads in their hands.

The left headlight of the van is smashed, but the taxi is in worse shape. It has a substantial dent. Before the police officers come over to Mancebo, they urge only those who actually saw the accident to remain and the rest to disperse.

Mancebo quickly glances up at the writer, who is still standing there after the officers’ appeal. Mancebo’s hands are now so sweaty that he finds it hard to move the wooden beads. Is my mission going to come to an end now, before it’s even begun, he wonders. If the writer comes forward as a witness, it’s all over. Then we’ll have a relationship, albeit a superficial one. He wouldn’t under any circumstances be able to continue observing the writer. He would no longer be just an anonymous man over the road, he would become the man who rammed into the taxi.

The taxi driver gives his version of events to the police and Mancebo is grateful for that, because he’s sure it’s correct. As for him, he has no idea what happened. The writer slowly starts to move away from the scene of the crime. The police advance on Mancebo.

My duties consisted of forwarding emails to Monsieur Bellivier. Every time a message came in, there would be a little pling. The log-in details were provided in the so-called contract of employment. I’d been allocated the email address [email protected] and was to forward any emails that arrived to [email protected]. Nothing was said about why these emails couldn’t be sent straight to Monsieur Bellivier. What was made very plain, however, was that I wasn’t to add, amend or delete anything from the emails; my only job was to forward them.

Strangely enough, I slept well the night before my first day at work, despite the heat which was paralysing the city. What I didn’t know was that it would be the last good night’s sleep I’d enjoy in a very long time, something that would have nothing to do with the heatwave. I shoved an extension lead in my laptop bag, even though I wouldn’t be needing it at my new job. Part of me was convinced I would be spending the day at the café after all.

There were a number of hurdles to negotiate on the way to my assignment. The first was the swing door into Areva, you could never trust those things, followed by a critical stage: reception. Maybe the receptionist would stop me. Maybe rumour had reached her that someone was trying to move in at the very top of the building. Using CCTV footage, they might have been able to identify the two people who ascended the tower block yesterday using fake passes. And in front of her on her impeccable desk she might now have the photos of the wanted individuals. A man and a woman. But only the woman would walk into the trap. Only she was stupid enough to return to the scene of the crime. And if the receptionist didn’t abort my mission, maybe my pass card would. Would it make the light go green? The fact that it had worked the day before didn’t really mean a thing. It could have a best-before date.

The last hurdle was the door to the office. Would the key fit? There was also no guarantee that the computer would work, that the log-in details would be correct, that any emails would arrive. It was all those critical stages, plus my own doubts, that made me pack my extension lead that morning. It seemed fairly likely that I would end up being a cyber nomad again that day, just like every other. I deliberated for a long time about whether to take one of my anti-anxiety tablets. In the end, I put them in my bag.

By the time I had changed my outfit twice, I realised that I really did care how I looked. It was a long time since that had happened. It was a long time since I had cared about anything at all. It would be an exaggeration to say I felt expectant, but I did care, and that was enough. For months I had dressed and packed my things without sparing a single thought to either my clothes or the contents of my bag. But today I did.

It’s hard to get dressed when you don’t know who you are. Nothing seemed right for who I was meant to be. The most logical thing might have been to wear the outfit I felt most comfortable in, something that was me, but that was what scared me most. It was like going on stage without a costume.

An unmanageable sense of insecurity came creeping over me, and I stole a glance at the tablets in my bag. The only way to handle the situation, maybe even make it pleasant, was to simply decide who I was. I made the rules, no one else. The others, whoever they were, would have to fit in with me. Or so I told myself, anyway. My pass became my identity card, and it said sales manager, so in the end I opted for a black skirt with a short-sleeved white blouse and red shoes. I looked at myself in the mirror and saw someone who looked just like me.

In a big city, you’re never really alone, and I was far from alone in walking towards the black skyscraper that morning. Despite that, I was probably the only one in that specific set of circumstances, I thought, clutching my laptop bag more tightly. Or was I? Maybe there were lots of people acting as pawns in a game they knew nothing about. Lots of people playing roles, carrying out apparently meaningless tasks.

The swing door hit me right in the face. No harm done, but it was like it had heard my fears. Maybe it was offended that I had doubted its competence. A dark-skinned man in a suit quickly asked if I was all right. I nodded and smiled. My heart began to pound. It was the same receptionist as the day before. She was on the phone, her eyes staring into the distance. Maybe she had the police on the line.

There were barriers on both sides of the reception desk. There might even be two lift systems, leading up to different sections of the tower block. I followed the stream of people to the left. If it hadn’t been for the incident with the door, I wouldn’t have felt so nervous. It was time to use my pass. I calmed myself down with the thought that if it didn’t work, if the light went red, all I could do was calmly turn round, leave the building and go back to the café. Nobody would notice a non-functioning pass. But the light flashed green and I hurried for the lift, not giving it the chance to change colour.

From day one, the lift became the place where I felt most secure. A limited amount of space, four walls, and everyone who entered it nodded and said good morning. They fascinated me. The women in all their femininity and the men in all their masculinity. Perfectionism reigned supreme, and I felt pleased with my choice of outfit. Finally alone in the lift, I was carried up towards my destination. The first thing I noticed when I stepped out into the corridor was that the lights were on. Maybe the skyscraper had an automatic lighting system. I decided that must be it. The top floor was silent as the grave. The lift began its downward journey and I walked towards my door. My red shoes were an attractive sight against the dark red carpet. Key in the lock. There was no one there, but I had already assured myself of that by peering in through the blinds. I left the door open. Everything looked different from yesterday. Maybe it was the light. I took my contract out of my bag as though doing so gave me permission to switch on the big computer. It took some time to start up, a

nd I gazed out at the Sacré-Cœur while I waited.

I logged in. My inbox was empty. Not even a welcome email from the operator. That meant someone else had used the account before me. I switched on my own computer. If this was all just a joke, I wasn’t going to lose any working time. I decided that if nothing happened by lunchtime, I would leave, and I started an article I should have tackled earlier. Devoting a few hours to something as banal as the tourist attractions of Paris felt good. It was like keeping one foot in the real world. And that was what I did, for a while, before that foot was dislodged by a loud pling. An email. I opened and read it, and a small smile played on my lips. I was happy that it was all true, that there really had been a pling.

I got straight up and closed the door. This was my office now. And though I knew what I had to do with the incoming email, I read the contract again, slowly, word by word. As though I’d suddenly lost confidence in my own abilities, I spelled out the address the email had to be forwarded to. The email itself consisted of a combination of numbers. An account number, perhaps. The sender was [email protected].

I pressed send as though performing some kind of ritual. Done. And before I stepped back into the real world I just sat there for a while, staring at the screen. Then I returned to writing about the most popular tourist attractions in Paris with a new-found energy.

There were a total of three plings before lunch that first day. It was as much fun every time. I had been living in a sort of haze for months, breathing in an atmosphere that felt impenetrable. It had been such hard going that I’d even sought help. Therapy and tablets, guilt and emptiness had filled my days. So how on earth could a totally meaningless task suddenly give me a sense of purpose? But it did. The work amused me. I’d been hoping for the chance of an exposé, a way of uncovering Areva’s dirty dealings in North Africa. But the more plings that came in, the more I realised it wasn’t going to be anything of the kind. There was never anything in the subject line, no title to the emails. The sender was always [email protected], and I worked out almost immediately that the numbers in the address were the postcode of the business district.

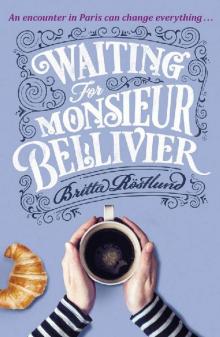

Waiting for Monsieur Bellivier

Waiting for Monsieur Bellivier